By Dr Fazlur Rehman (Research Scholar) and Dr Jan Nisar Moin Freedom Fighter (Tilangana)

Reconciling Representation, Federalism, and Democratic Equity

In the grand mosaic of Indian democracy, the question of delimitation looms large, perched precariously at the intersection of proportional representation and federal harmony. As the nation treads towards the imminent 2026 review, it finds itself grappling with fundamental concerns:

should parliamentary seats be dictated solely by demographic weight, or should developmental indices and governance performance inform this redistribution?

This article navigates the historical evolution of Lok Sabha seats, the fraught federal challenge of seat allocation, the underrepresentation of Muslims in electoral politics, and international models that offer instructive parallels.

In doing so, it endeavors to chart a course toward a judicious, equitable, and future-ready political dispensation.

Delimitation, the periodic redrawing of electoral boundaries, stands at the crossroads of representation, federalism, and democratic equity.

This study explored the intricate balance between equitable political representation and federal integrity, ensuring that electoral divisions reflect demographic realities while upholding democratic fairness. It aims to analyze the impact of delimitation on governance, social harmony, and political stability.

Understanding the delimitation process is crucial for fostering a just democracy. By examining its implications on power distribution and regional representation, this study sheds on ensuring fairness, preventing marginalization, and strengthening democratic institutions.

A Historical Perspective

The evolution of India’s parliamentary representation has been a tale of adjustments and recalibrations. The first delimitation in 1952, under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, established 489 Lok Sabha seats.

Subsequent exercises in 1963 and 1973—both necessitated by demographic expansion—raised this number to 522 and 543, respectively. However, the political zeitgeist of the Emergency period witnessed an extraordinary intervention: the 42nd Constitutional Amendment (1976) froze seat redistribution based on the 1971 census.

The rationale? To incentivize population control. This freeze was prolonged by the 84th Amendment in 2001 under Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s government, effectively deferring the next realignment until 2026.

As that year looms, the debate has reignited, particularly in India’s southern states, which have exercised demographic restraint yet now face the prospect of reduced parliamentary influence. Conversely, northern states—where population growth has been more pronounced—stand to gain a disproportionate share of seats.

This raises a disquieting conundrum , should population alone dictate representation, or must governance efficacy, economic contribution, and social advancement be factored into the equation?

The Federal Quandary: An Electoral Tug-of-War

At its core, federalism demands that political representation encapsulates the aspirations of all regions equitably. However, the impending delimitation exercise threatens to destabilize this delicate equipoise.

Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan have experienced exponential population growth, while Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh have, with judicious policy interventions, curtailed their fertility rates.

The paradox is striking—those who embraced responsible governance may paradoxically find themselves politically marginalized.

This debate is neither trivial nor merely theoretical. It carries weighty political ramifications. If representation is dictated purely by numerical strength, northern states could dominate policy discourse, potentially marginalizing the economic and social advancements spearheaded by the south.

The pressing question, then, is whether India can architect a model that respects the federal spirit without undermining democratic equity.

Projected Impact of Delimitation by 2026

| State | Current Lok Sabha Seats | Projected Seats (Based on Population Growth) |

| Uttar Pradesh | 80 | 110 |

| Bihar | 40 | 58 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 29 | 40 |

| Rajasthan | 25 | 35 |

| Tamil Nadu | 39 | 32 |

| Kerala | 20 | 15 |

International Insights: Lessons in Electoral Design

A perusal of global practices reveals diverse approaches to representation. The United States, for instance, has maintained a cap of 435 seats in the House of Representatives since 1913, periodically redistributing them based on the “method of equal proportion.”

The European Union, conversely, employs “degressive proportionality,” ensuring that smaller nations retain an equitable voice despite their modest populations. Germany’s mixed-member proportional system offers another instructive model, balancing constituency representation with party-based proportional allocation.

These paradigms demonstrate that representation need not be a crude arithmetic exercise but can be nuanced to reflect both population and federal integrity.

Muslim Representation: A Democratic Deficit

Political representation is the linchpin of representative democracy, yet the persistent underrepresentation of Muslims in India’s legislatures underscores a systemic democratic deficiency.

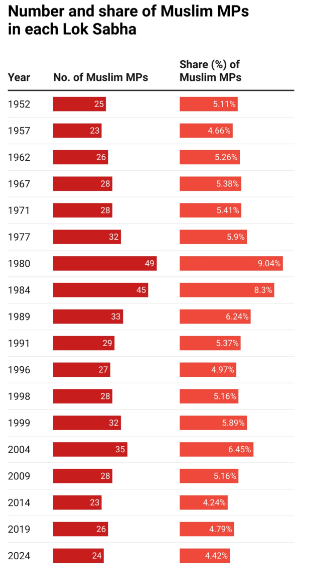

Despite constituting approximately 14% of the population, their presence in the Lok Sabha has remained abysmally low, rarely exceeding 6%. The 18th Lok Sabha (2024) saw only 24 Muslim MPs, with no representation from the ruling party.

This trend, however, is neither novel nor solely attributable to the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Historically, even during the Congress-led decades, Muslim political visibility remained stunted.

Between 1952 and 1977, when Muslims constituted roughly 10% of the population, only about 4% of candidates fielded by major political parties were Muslim. In 1980, Muslim MPs accounted for 9% of the Lok Sabha, a number that has since dwindled despite the community’s growing demographic share.

By 2014, while Muslims made up 14% of India’s population, their parliamentary representation had shrunk to a mere 4%.

One major contributing factor is the first-past-the-post electoral system, which disadvantages dispersed minority groups. Additionally, the reluctance of mainstream political parties—including Congress and regional outfits—to field Muslim candidates due to perceived electoral risks has exacerbated the issue.

In 2024, for instance, Congress did not nominate a single Muslim candidate in states like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, or Gujarat, and the overall number of Muslim candidates fielded across parties hit a historic low of 94.

The delimitation process, too, has inadvertently curtailed Muslim electoral influence. Constituencies with significant Muslim populations have been redrawn or reserved for Scheduled Castes, effectively diminishing their political clout.

Uttar Pradesh, home to over 40 million Muslims, has no BJP MPs or MLAs from the community, and the same pattern extends to states like Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh.

Moreover, the erosion of Muslim representation is evident even in the Rajya Sabha. Traditionally, parties had informally balanced the community’s underrepresentation in the Lok Sabha by nominating Muslims to the upper house, where indirect elections offered a buffer against majoritarian pressures.

However, Muslim representation in the Rajya Sabha has also declined from an average of 12% to just 7% today, further limiting their legislative influence.

To remedy this democratic deficit, future delimitation must incorporate socio-demographic considerations, ensuring that constituency boundaries do not inadvertently disenfranchise Muslim voters.

The question, ultimately, is whether India’s democracy can genuinely reflect its pluralism or whether electoral mechanisms will continue to structurally marginalize one of its largest minorities.

Despite constituting approximately 14% of the population, their presence in the Lok Sabha has remained abysmally low, rarely exceeding 6%. The 18th Lok Sabha (2024) saw only 24 Muslim MPs, with no representation from the ruling party.

This democratic deficit is attributable to multiple factors: the first-past-the-post system, the political hesitancy of mainstream parties to field Muslim candidates, and the manner in which constituency boundaries have been drawn.

The delimitation process, in its past iterations, has inadvertently curtailed Muslim electoral influence by reserving Muslim-majority constituencies for Scheduled Castes. To remedy this, future delimitation must incorporate socio-demographic considerations to ensure political inclusivity.

Bridging the Representation Gap: A Constructive Way Forward

Drawing from the insights of Hilal Ahmed’s research, a few correctives merit serious consideration:

- Proportional Representation Hybrid: Adopting elements of a mixed-member proportional system, akin to Germany’s, could ensure fairer representation for marginalized groups.

- Redistricting with Equity: Future delimitation exercises should safeguard minority electoral strength rather than inadvertently diluting it.

- Party Incentivization: Political parties should be encouraged to field a diverse slate of candidates, reflecting India’s pluralistic ethos.

- Strengthening Local Governance: Robust panchayati raj institutions and municipal bodies can supplement parliamentary representation.

- Political Awareness Campaigns: Enhancing voter mobilization among underrepresented communities can foster greater political participation.

A Balanced Approach: Reimagining Delimitation

How, then, should India approach its impending delimitation? A few pragmatic solutions emerge:

- Capping Lok Sabha Seats at 543: Retaining the existing number while internally redistributing them could mitigate regional tensions.

- Augmenting State Assemblies: Expanding state legislatures could strengthen grassroots governance without unsettling parliamentary dynamics.

- Weighted Representation Model: Balancing population-based seat allocation with governance performance metrics could yield a fairer outcome.

- Gradual Implementation: Phased seat adjustments could prevent abrupt power shifts and ensure smoother transitions.

- Reserved Representation for Women and Minorities: Drawing inspiration from Rwanda’s gender quotas and Canada’s indigenous representation, structured reservations could bolster democratic inclusivity.

Towards a Future-Ready Democracy

The 2026 delimitation exercise presents India with both a challenge and an opportunity. A purely population-driven model risks entrenching electoral hegemony in high-growth states, while a federalist correction could distort democratic representation.

The path forward necessitates a nuanced equilibrium—one that acknowledges demographic realities while rewarding governance performance.

The Indian polity has long prided itself on its ability to reconcile diversity within a unified framework. It must now extend this ethos to the realm of representation.

As debates intensify, the onus falls upon lawmakers to sculpt an electoral architecture that is both just and judicious, safeguarding the federal compact while upholding the sacrosanct principle of democracy.

The decisions of 2026 will reverberate far beyond the corridors of power, shaping the nation’s democratic trajectory for decades to come. A forward-thinking, inclusive, and strategically calibrated approach is not just advisable—it is imperative.

..ensuring equitable democratic participation. A hybrid approach, integrating proportional representation and governance-based weighting, could mitigate regional disparities while preserving the nation’s pluralistic spirit.

Political inclusivity, particularly for underrepresented communities, must be a guiding tenet, with constituency redistricting executed in a manner that upholds electoral justice. Furthermore, a measured, phased implementation of seat realignment could prevent abrupt disruptions.

India stands at a historic juncture—balancing demographic imperatives with the principles of federalism will not only define the 2026 delimitation but also shape the nation’s democratic ethos for generations to come.