Is Ayodhya in District Faizabad itself the Epic Ayodhya or not?

Abdul Rasheed Agwan

The Ayodhya controversy has become an insurmountable academic puzzle of our age with the riding question, whether any real Ayodhya had ever existed; particularly, is Ayodhya in District Faizabad itself the Epic Ayodhya or not? It too has become a political and legal puzzle by this time.

This whole illusion is the product of a customized, crafty and compromised history of Ayodhya that has emerged from a power game since the takeover of Oudh by the East India Company in 1764, and then subsequently sustained by the British Empire and some political sections after the Independence.

The most remarkable change in this regard is the transformation of a locality Awad/Oudh into an epic Ayodhya. A Jesuit agent of East India Company, Joseph Tieffenthaler, noted in memoirs of his stay at the town during 1766-1772, “This is Oudh, learned Hindoos call it Ayodhya.”

One and half centuries before him, the Company’s another agent, William Finch, recorded the name to be just ‘Oude’ where he visited in 1610. Does the above statement make any difference for our understanding about Ayodhya? Yes and definitely.

It appears from the local history that Oudh and Ayodhya are not synonymous but the latter nomenclature has systematically been transposed on the former for creating an illusion that this small, unassuming town, long known as Awad or Awadh, should be taken as the epic Ayodhya.

For both, the local people and the official documents, throughout the Muslim and British periods, the place remains as Awad or its variant Awadh, rather than Ayodhya.

During the Sultanate period, the area and the place was known as Iwaz. AlBeruni, who took journey of the region almost a century before the establishment of Sultanate rule in India, did not mention even that, though he identified a place from the same region, called ‘Bari’. That means, Iwaz came into existence long after him.

Iwaz is a Turkish form of an Arabic word Awad, means beautiful. Apparently, the frequent use of Iwaz or Awad for the scenic place or the area in its early days, gave it a homonym, Awadh, i.e. not to be killed. Even up to the time of Tulsidas the place was not known as Ayodhya.

He constantly uses in his compositions Awadh and Awadhpuri for it. He did not list Awadh or Ayodhya among holy pilgrimages of his time.

It seems that with the establishment of the first ever Vaishnavite sect in the form of Srisampradaya of Shatrughna Acharya at Awadh during the 16th century, as Hans Bakker informs, an elite section started depicting the place as Ayodhya of Ramayana, whom Tieffenthaler terms later on as “learned Hindoos.”

This section comprised a small minority of Ramvatas for a long time, as could be understood from the 1889 census of Oudh and many later events. Shaivite Rajbhars, Pasis, etc comprised dominant population of Oudh until the close of 19th century who used to call the place as Bareta and the local river as Diva. Many British documents have noted this fact.

Perhaps, the most vital evidence regarding the early religious history of Awad comes from the time of Qutbuddin Ebak. His contemporary historian, Hasan Nizami, describes his conquests in north India and mentions that he destroyed temples of Ghuram, Merrut, Devgiri and Benaras.

Ebak’s journey through Iwaz was recorded by Nizami but nothing had been mentioned regarding any temple there. Obviously, the place was either not populated at all by that time or there were no temples to give Ebak an opportunity to destroy them.

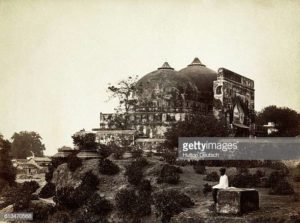

William Finch mentions existence of two ruined castles and some houses at Oude, when he visited it during the period of Emperor Jahangir but he also did not saw any temple there. Of the two relics seen by him, the Fort of Pathan was said to be four hundred years old whereas the time period of the Fort of Ranichandi was not mentioned by him.

May be it was already in ruins before the Turkish period began, which led to construction of another fort in its vicinity during the 13th century.

Three facts are conspicuous from the local history. Firstly, the place was locally known as Awad or Oudh, which became gradually populated during the latter Sultanate period.

Secondly, there were no ancient temples at Awad. The name Ayodhya for the place got currency only after mid-18th century, which was used only by a small section of people, even up to the advent of 20th century.

The question arises how then a lot of historical, archaeological and textual proofs are there to substantiate the Ayodhya theory? The answer to this question is that they were manufactured to develop a customized history of Ayodhya, i.e creating history according to the vested needs.

We have a similar contemporary instance wherein Ranapratap is declared victorious against Akbar to boost the communal aggrandizement, though the fact is contrary.

There are three distinct phases of transforming Awad into Ayodhya. Firstly, there is an ideological phase influenced by Ramanandacharya, Tulsidas, Shatrughna Acharya and others, who popularized Ramakatha among common people of the region as a strategy to counter the spread of Islam. Then follows a realization phase in which the abstract Ayodhya was created on the ground with the collusion of East India Company and members of the Ramvata sect.

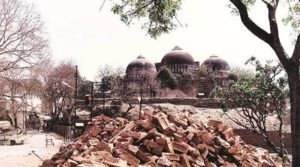

The textual references of Ramakatha were interpolated, historical facts were created, relics were purposefully interpreted, Janmasthan was claimed and people become divided on communal lines. The Company got the major dividend of the situation and succeeded in establishing its hold in most parts of north India.

The current phase can be termed as the legitimization phase, which began with the court verdict of 1886. The appertained case in the Supreme Court was the final battle to seek that legitimization for a non-existent Epic Ayodhya at Awadh.

There is no doubt that the epic Ayodhya enjoys great significance in the Indian life and culture and also as a literary master piece of poetic imagination, as Valmiki himself has endorsed in the Ramayana in his statement, “So sings the poets.”

However, Ayodhya as a grand city of antiquity at Awadh seems dubious and highly improbable.

****

(The contributor is an author of several books )